Mike Kerrigan is an attorney who practices in Charlotte, North Carolina. His firm's website says that his law practice focuses on "the purchase, sale and trading of loans, securities, claims, derivatives and other interests in domestic and international companies in, near, or emerging from, financial distress." A guy like that, clearly, can be expected to read

The Wall Street Journal (but of course, I read it, too - which is maybe somewhat less expected).

Anyway, Kerrigan not only "reads"

The Wall Street Journal; he has written an opinion column for the paper, too, which was published on August 10, 2023.

That column presented what Kerrigan calls his "Sweater Theory."

I am actually more interested in Kerrigan's "Fake It Till You Make It" discussion - part of that same column - but I can provide the following about Kerrigan's "Sweater Theory," since I do think that his point, with reference to "sweaters," is well taken:

When any of my admittedly fortunate kids has voiced an opinion to the effect of “everything would be perfect if only X,” they invariably confront their dad’s “sweater theory” of life.

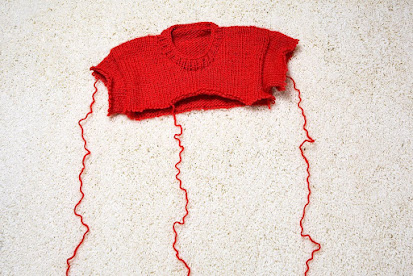

The sweater theory reminds that life is an all-or-nothing proposition, an inestimable gift with no “if onlys.” Like pulling on the loose thread of a sweater, a seemingly innocent endeavor risks entirely unraveling the pullover, leaving things not slightly better but dreadfully worse.

Imagine my joy to learn that in “Orthodoxy,” G.K. Chesterton’s apologetical masterwork, he warned the following: “Do not free a camel from the burden of his hump; you may be freeing him from being a camel.” There was my sweater theory pithily stated (emphasis added).

Life, Kerrigan is reminding us, is basically a "package deal." We have to "take the bad with the good," and if we aren't willing to do that, and try to unravel one strand of our lives from the whole of it, we're likely to go way off the rails and lose everything.

Good point! Hopefully, this is not the first time you have confronted that reality of our human existence, even if, like me, this is the first time you have heard this insight characterized as a "Sweater Theory."

As earlier noted, while I was pleased to get Kerrigan's reflections on his "Sweater Theory," I was more interested in what Kerrigan had to say about a life strategy generally known as "

Fake It Till You Make It." You probably well understand this life principle - and perhaps you even practice it yourself, but if that is not the case, and if you happen to be a little hazy on the idea, you can click the link to get a definition from

Wikipedia. Here is how Kerrigan presents the "Fake It Till You Make It" idea, which he clothes in the lineaments of spirituality:

“Fake it till you make it” is motivation I draw on frequently when I know the good I’m supposed to do but in my weakness, I don’t feel like doing it. What a comfort to discover that before I was born, C.S. Lewis had already provided the underpinnings for this philosophy.

In “

Mere Christianity,” Lewis advised: “Do not waste time bothering whether you ‘love’ your neighbor; act as if you did. . . . When you are behaving as if you loved someone, you will presently come to love him.” What a confirmation: Not only might the faking it be brief, the making it might carry me all the way to heaven.

It is thrilling when sound theory holds up in practice. It is scarcely less wondrous when sound practice holds up in theory

To my way of thinking, Kerrigan is discussing, in these remarks, a topic that I think is quite important; namely, the relationship between "thought" and "action." Like Newton's "First Law of Motion,"

about which I have commented before, we can only change the world - and change the realities we inhabit - if we take "action," if we "do something" - usually something new and unexpected.

Before we can "act," though - at least in most instances - we need to have an "idea" of what it is we want to accomplish, some "theory" that tells us what we think we might accomplish by our action. Such an "idea," or "theory," is a requirement, because we base our actions on the ideas we have. No "idea," no "action." In the end, however, it is the "action," not the "theory," or the "idea," that makes all the difference.

This observation is accurate with respect to what we do by way of our "individual" actions, and it is also accurate with respect to what we will do "collectively" - or "politically," as I would say.

Kerrigan's point, however - and it is a rather important point - is that trying to develop the perfect "theory" can sometimes mean that we defer "action," and when that happens, our efforts to perfect our "idea" about what to do can lead us to fail to do what we must do (and what we genuinely want to do).

This point, I believe, is at least as important as that "Sweater Theory." Really, Kerrigan is telling us, we can call our actions "faking it till we make it," if we want to, but we can't wait around for the "perfect theory," the "perfect plan." Our time is limited, and the challenges we face are real. We need to take "action," not just think about whether we should. We need to be pretty prompt about taking important actions, too, once we have some initial idea of what we think might be called for.

Global warming (on the "collective" front) is a good example of the principle. It is time to "do" something about it, even though we may not have, to our full satisfaction, a perfect "theory" to describe what we think would be the best thing to do. We know some things to do, don't we? Well, let's start doing them!

You can call that kind of approach "faking it till we make it," but the key thing, the most important thing, is to take the actions we can now envision. Let our actions prove the theory!

"Action" is the key, and if you haven't read Hamlet recently, now might be a good time to revisit one of Shakespeare's greatest works. The quotation below, I think, should be familiar, if you have ever read, or seen Hamlet, one of Shakespeare's greatest plays:

The native hue of resolution is sicklied o'er with the pale cast of thought; and enterprises of great pitch and moment, With this regard, their currents turn awry, and lose the name of action.

"Fake It Till You Make It?" Let's not allow our fear of "faking it" - a fear of not really having the perfect solution - prevent us from taking the actions we think may be able to address the dire realities we confront, on so many fronts. We can play "Hamlet" to the world crisis of global warming, but that would be a mistake.

Let's not miss our chance to save the world.