Judge John Hodgman, who is not, as I deduce from his Wikipedia entry, actually a judge, shows up each week in The New York Times Magazine, his face, name, and bogus title associated with a column titled, "The Ethicist."

Upon closer scrutiny, it becomes clear that not only is Hodgman not a judge, he isn't even the author of the column. Kwame Anthony Appiah, a British-Ghanaian philosopher, cultural theorist and novelist, is the guy responsible for providing answers to the ethical, or quasi-ethical questions put to him by readers of The Times. You know, questions like this: "Should I tell my best friend's wife that her husband is cheating on her?"

I am a regular reader of "The Ethicist," so I saw Appiah's December 6, 2020, answer to a reader who asked this pertinent question:

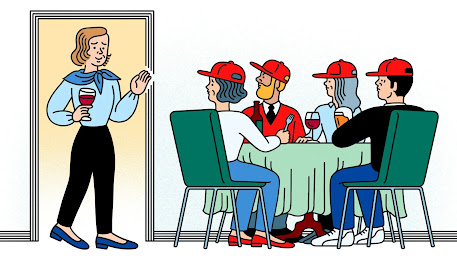

Should I Stop Speaking to My Trump-Supporting Friends?

What? I thought to myself. You have friends who support Trump? What state do you live in? Levity aside (levity being ever less appropriate after the invasion of Congress by a mob spurred on by our current president), the question goes to an important issue. How do we provide proper care and sustenance to a "body politic" that contains those who hold such extremely different and polarized opinions about politics and related issues?

Here is what "The Ethicist" had to say about the reader's question:

The polarized state of our politics, alas, means that people are so taken up with their political identities that they’re unable or unwilling to consider the views of those outside their political tribe. Conversations on these topics tend to turn up the temperature while dimming the lights. And, given your principles, it’s easy to assume that your Trump-loving friends are morally defective — that they don’t take cruelty, xenophobia, intemperance, narcissism and dishonesty with due seriousness.Perhaps that’s the case. But perhaps the gulf between you and these friends arises from differences in your epistemic capacities — the ability to gain reliable information. Our beliefs depend not just on our own brains but also on the social worlds we live in. One way of capturing this truth is what some philosophers have called the extended-mind hypothesis: Our minds don’t simply repose between our ears (the argument goes) but extend into the world around us, a world that may or may not include Fox News, Parler, talk radio, a voluble workplace colleague who has always seemed marvelously in the know, filtered Twitter feeds and the like. What’s obvious is that people can be epistemically disadvantaged by gaining their beliefs from social networks that are radically unreliable. We get many of our false beliefs in the same way we get true ones: by listening to the views of people we trust. You can be partially responsible for being in an unreliable network if there are signs that something is wrong and you don’t examine the possibility that it’s misleading you. But the misjudgment here may not reflect bad moral values (emphasis added).

It seems to me that "The Ethicist" is doling out some pretty good advice here. We need to be able to continue to provide entry to the very "big tent" that includes all of us, and our commitment should be, always, to be willing to meet with each other, and talk, whoever we are, whatever we think, and whatever the color our skin, our gender identification, or the size of our bank account.

Is that too idealistic?

Some may think so. Call me an idealist!

Image Credit:

https://www.nytimes.com/2020/12/01/magazine/should-i-stop-speaking-to-my-trump-supporting-friends.html

No comments:

Post a Comment

Thanks for your comment!